‘The House’ progress: Boy meets girl, boy dumps girl, boy makes allusions to pie

Thanks for following along with my writing project, The House, a historical novel-in-progress about colonial Australia’s Sarah Wentworth, a ‘currency lass’ born as a free person to ex-convict parents. Sarah brought the first breach of promise case in Australia, and faced a life of social exclusion, even though she was married to politician William Charles Wentworth, known as ‘Australia’s greatest son’.

NSW State Archives Reading Room

Last Friday morning I got in my car and travelled for an hour on the motorways out to the NSW State Archives Reading Room in Sydney’s west. The building was surrounded by secure high fencing, with a serious gate and security cameras. On my way in, I had to stop to talk to the guard on the gate, and the uniformed security officer at the front door, and let them know of my intentions for my visit.

My intentions were honourable, by the way.

I was there to look at the original court papers from Cox v Payne, Australia’s first breach of promise case, in 1825. In this case Sarah Cox argued that John Payne’s intentions and actions towards her were not honourable, and that he should pay her 1000 pounds for not fulfilling his promise to marry her.

It was a fun morning. Old papers are amazing. They look incredible when they’re photographed, but they’re so much more real when you see them in person. I had to use gloves to touch them, and nifty fabric weights to flatten out the papers so I could photograph them. I came away feeling that I had a better understanding of the case, and of the players in it.

Cox v Payne is a notable case in the legal history of colonial New South Wales. It helps us to gain a fuller understanding of gender relationships, and marriage and family at the time.

But it also plays an important part in Sarah’s personal story.

It helps me understand where Sarah came from, what has shaped her, and what she values.

It marks the beginning of Sarah and William Charles Wentworth’s relationship (and their family… more on that in a future episode of this blog).

It shows me that Sarah was a woman of action.

It also gives me clues about how she may have been steered, guided… or exploited? by the various men in her life (again — more on that later).

While the State Archives trip was worthwhile, I’m glad I didn’t have to rely only the original archived court documents while researching Cox v Payne. Everything is handwritten, for obvious reasons, and it takes ages to read. I was grateful they let me photograph it so that I can bring it home and spend time transcribing. I’m also grateful for whoever decided to digitise the old colonial newspapers which reported on the case back in the day. The Australian report published on 19 May 1825 is found here, and the Sydney Gazette report of 17 May 1825 is found here.

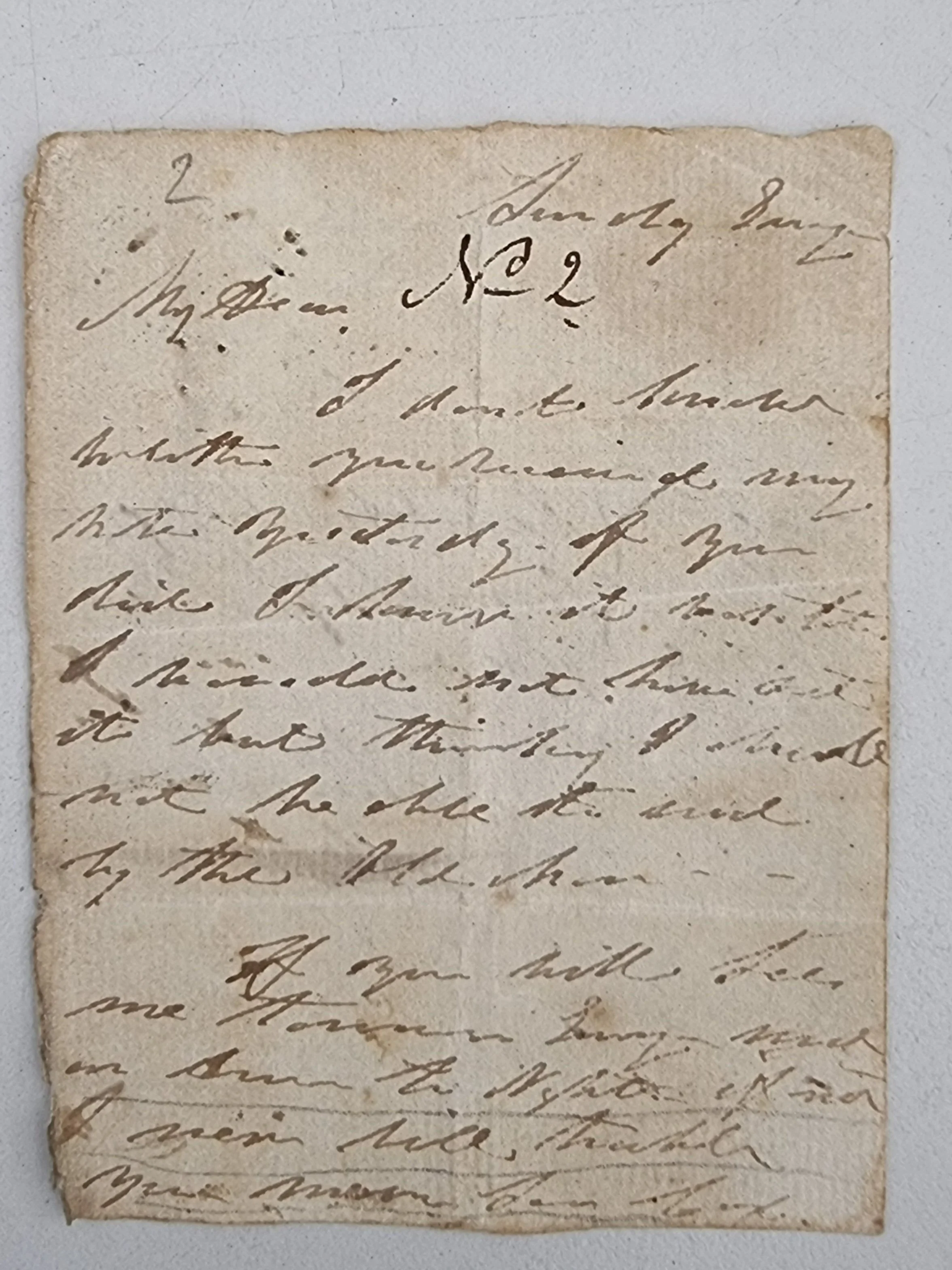

Some of Sarah Cox’s letters were exhibits and evidence in Cox v Payne. These images are photographs of Sarah’s letter No. 2. I have yet to decipher her handwriting.

Cox v Payne: the back story

Here’s the story of what led up to the Cox v Payne breach of promise case in 1825.

Sarah Cox was the oldest of three daughters, born to 1805 to Francis Cox and Fanny Moreton. Francis and Fanny were emancipated convicts who by 1810 were living freely in Sydney. Sarah grew up around what is now Circular Quay, on the Opera House side, where Francis had a blacksmith’s business.

While she wasn’t badly off, Sarah didn’t have many ways to get ahead in life. Unlike some emancipated convicts, and most free settlers in New South Wales, who did very well for themselves very quickly, Francis Cox didn’t seem to have the entrepreneurial ability to start successful businesses and farms to make him or his family rich. He supported his family adequately as a blacksmith but did not much more than that.

At age 16, Sarah got herself an apprenticeship as a milliner with a Mrs Foster*. She had recently arrived in Sydney and set up shop not far away in Castlereagh Street. At some point Sarah moved in with Mrs Foster, which seems to be normal for apprenticeships at the time. As well as having a job, very soon, she had a ‘young man’, although ‘young’ is debatable and these days the age difference between a girl of 16 and a man in his early 30s is, well, …problematic…, but this is the history, and that’s what happened.

In 1822, John Payne was a ship’s captain sailing and trading between Sydney and Port Dalrymple on the north coast of Tasmania. He may have met Sarah while dealing with her father around ship-related metal blacksmithing jobs, or he may have met her at Mrs Foster’s shop when he collected letters to be delivered to Tasmania. Either way, she caught his eye, and pretty soon he was ‘in the habit of going backwards and forwards to the house.’

The romance

To begin with, Payne had good intentions. He did the right thing and asked Francis if he could court Sarah, declaring his views as being ‘the most honourable’ and expressing ‘the hope of being allied to the family.’ He also put it in writing, asking in a letter if she had any objection to changing her name to ‘Sarah Payne’. She doesn’t appear to have had any objections; in fact, it was quite the opposite.

I don’t imagine that he gave her an engagement ring to seal the deal like we do these days. They weren’t rich, and the giving and returning of a ring was never mentioned in the reporting of the case. Rings aside, it quickly became publicly known that John Payne would eventually marry Sarah Cox.

At this point, Payne wasn’t expecting that the marriage would benefit him financially. When he asked permission to court her, Sarah’s parents said to Payne, ‘She has no fortune.’ Payne replied, ‘I do not seek one.’

The reality

The relationship progressed by letter when Payne was away at sea, and by visits when he was back in Sydney. It was when he left maritime life in 1823, moved back to Sydney full-time and took up a brewing and soap making business on George St, that things started to go wrong between them.

For a start, he liked a drink. This would have been very much part of Sydney life then, as it is now, but Sarah wasn’t impressed when Payne turned up dead drunk at her parents’ place very late one night and created a scene. She shut the door in his face, told him to never come near the house in that state, and got her brother in law to help her write an angry letter, saying that if he couldn’t ‘select any hours but those he had better stop away.’

They made up (Sarah wrote an apologetic letter basically saying ‘sorry for overreacting’) and at some point Payne told Sarah’s sister that he hoped his ‘eyes might drop out of his head’ if he did not marry Sarah Cox.

But around him, Payne could see Sydney businesses growing, and people getting richer. On paper, his own businesses — a farm, a mill and house rented in George St — looked like they were doing alright, but there are hints that perhaps he wasn’t as successful as he appeared.

The temptation

By 1824 Payne was playing a side game. Lured by the idea that he could marry money, he kept his engagement to Sarah Cox going, but began visiting Edward Redmond’s home. Redmond was a wealthy emancipist merchant who had a wine and spirit licence, land at Botany, and two (no doubt delightful) daughters by the names of Mary and Sarah, one of which would eventually inherit all of Daddy’s money.

Tales of these visits made their way to Sarah, who wrote to Payne saying she was unimpressed, and demanding her own letters back. Things might have been over forever, but Miss Redmond was clearly not interested (or perhaps her father put a stop to it) and Payne came back to Sarah, contrite and ready to resume their relationship.

In April or May 1824, Payne didn’t visit Sarah for a period of about three weeks. She heard nothing from him until the news came that he was married — to a woman whose own husband had only died several weeks ago!

It’s not surprising to learn that Sarah Sherwell**, the ‘other woman’ in this case, was wealthy. She had inherited a tidy sum from her husband, William Leverton, an investor in a milling business, who sadly exited this life at the age of only 34. Sherwell was clearly not too overcome by grief at losing William because she happily and quickly accepted Payne’s proposal and they got married.

The aftermath

Sarah Cox’s long, tumultuous engagement was over, and she was devastated.

Payne had dumped her in the worst way possible, and he wasn’t sorry. In fact, when he was confronted by Mrs Beckett about his deception, and asked why he did not marry Miss Cox after all his promises, he said casually, ‘Promises and pie-crusts were made to be broke.’ (By the way: I’m going to write that scene in a bakery. Payne is going to purchase a pie, break off a piece of the crust and eat it in front of Mrs Beckett. He’ll then nonchalantly leave the shop.)

There was more damage to come: Payne would not return Sarah’s letters, which threatened her privacy. And now stories about Sarah’s reputation were being spread around Sydney — probably by Sherwell’s sister, who had a vested interest in protecting the newlyweds, and no loyalty to her new brother-in-law’s former fiance.

Aged just 19, Sarah Cox was facing an uncertain future. She had lost the man she thought she loved, and the hope of marriage to him. She was humiliated in her close community, facing vilifying attacks on her reputation, which might have ruined her. She still had her job in millinery, but making hats may no longer have looked as attractive to her, after believing for so many years that she would marry a ship’s captain and businessman.

As well, suddenly, she found herself dealing with an annoyingly persistent new suitor, the appropriately named David Sutor, who wrote flowery letters and sent useless gifts of parrots, all with the aim of getting her to marry him, leave her home and family in Sydney, and live a whole new life in the bush in the middle of nowhere on the NSW south coast.

What was she to do? Sarah’s answer arrived on a ship in July 1824, in the form of William Charles Wentworth, back in Sydney after eight years away training to be a barrister. He was young, energetic, motivated, very ready to start all and any court proceedings… and he took a house pretty much next door to the Cox family on Macquarie Place.

Sarah’s world was about to change — in all the ways. Stay tuned.

*For those of you interested in Australian colonial history: Mrs Foster was the sister of the notable Mary Reibey who has an incredible story and is pictured on the Australian $20 note.

**Sarah Sherwell / Shurwell / Sherwel (Junior) was also an emancipated convict. She was transported from England on the Northampton in 1815 with several members of her family, also convicts, and had seen her mother die during the voyage.

My telling of Sarah Wentworth’s story has the working title of ‘The House’. If you’d like to follow along with my progress, I’ll be updating my subscribers every month or so, sharing story snippets and research discoveries, and talking through the process of taking on such a project. Sign up below to follow along. And drop me your comments and questions. I’d love to know what you think of the story and the project.

Catch up with the project from the beginning. Here’s the very first post introducing ‘The House’.